Memorie di Adriano | Architetture Olivettiane

A place from where to start again. Timeless architecture that when seen today still expresses the same suspended beauty as in the black and white photograph taken when it was built. These buildings are now candidates to become a UNESCO world-heritage site, in order to make them known around the world. Such an initiative will save these buildings and its locations — the interstitial spaces of which have gradually been tainted by money-oriented intrusions and urban “distractions” — but it will also allow us to see ourselves through the eyes of others, reminding ourselves of what we experienced in this corner of Canavese, on the edge of the Empire. It was late in the winter of 1960, 27 February, when Adriano Olivetti passed away suddenly and all of Ivrea stood still. It was carnival time and the celebrations were cancelled. The void left by Adriano was filled only with bewilderment.

The Office Block designed to contain all the company’s management functions in one place had just been commissioned, but financial problems within the company meant it could not complete the somewhat exotic outside design by landscape architect Pietro Porcinai. Entering the lobby and coming face to face with its central staircase — hexagonal in plan and serving the three blocks joined in a helix form — is a stunning experience. This is architecture that envelopes, hypnotises and alienates you, pushing the gaze upwards to a vaulted ceiling covered with hexagonal glass scales shaped like prisms that remind you of an industrious beehive. The story of the Olivetti venture is the story of an organic idea, developed in nearly every field of human knowledge and action. What remains of all that, today, is the way it took concrete form in architecture; describing the form and function of some of the most typical examples is a way of recalling the significance of the idea. The Olivetti kindergarten opens in 1941. Architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini applied autarky to the letter in the elegant citation of the genius loci of the city in the hills of Ivrea. They mocked the rhetoric of Fascist architecture, designing functional spaces arranged in Rationalist parallelepiped blocks with a skin of local stone. The garden follows the contours of the dioritic rocks, the pergola has pillars cut like the stone posts used to support vines, previously abundant in these parts, and the pool, no longer there, was where generations of children played under their teachers’ eagle eyes. The internal layout was purpose-developed for the different activities and became a model; and there were custom-designed wooden toys such as the elephant-slide and large baskets-on-wheels used to transport little guests.

Not far away, on via Jervis, where most of the original company buildings stand, Figini and Pollini left another indelible sign in the Social Services building, constructed between 1955 and 1959, which played on the modularity of the hexagon. A ribbon structure divided in two, one section contained an infirmary and the other gave employees an opportunity for cultural advancement with a constantly restocked library specialised in certain areas such as non-fiction and social sciences. It is no coincidence that it sat opposite what started it all: the factory. Actually, the factories: at the beginning of via Jervis is the industrial bare-brick building where Camillo Olivetti installed his precision-mechanics workshop in 1908 and where he produced his first typewriter. A series of extensions appeared next to this, all designed by Figini and Pollini. The two architects built the first modern plant between 1934 and 1936 and it contained the Salone dei 2,000 (The room of the 2,000), a meeting room that could accommodate all the then 2,000 Olivetti employees. A few years later came the 2nd and 3rd extensions of the Officine I.C.O. (Ingegner Camillo Olivetti), Rationalist buildings with glazed façades that were completed in the late 1940s. The Nuova I.C.O premises, built between 1955 and 1957, completed the series. South of the row of factory buildings is a canteen designed by Ignazio Gardella in the mid-1950s but now unrecognisable; its interiors have been broken up, emptied of their furnishings and are bustling with assorted activities. Follow the external perimeter, however, also developed in hexagonal form, and you will have the disorientating impression of being in Scandinavia, surrounded by the rocks and trees of the natural vegetation of Mt Navale. Here, meals were prepared by an early form of the short production chain, with raw ingredients from local agricultural concerns active in the company sphere of the so-called I-Rur (Istituto per il Rinnovamento Urbano e Rurale del Canavese). Equally, this was where leading names from the post-WWII Italian culture and art worlds performed or spoke on an almost weekly basis.

This architecture, with its functions and minutely detailed design, conveys a business mechanism based on efficient “principles of scientific management”. As early as the 1930s, company policy centred on the importance of developing a skilled workforce with no discriminations and conserving it by investing in constant training. Work health and safety were regulated and the company boosted worker loyalty by developing social services (nurseries and schools) and a transport network and by granting loans to refurbish the homes of employees in the hinterland of Ivrea. By the time Adriano gained full control of the company, he was firmly convinced that product quality was inseparable from aesthetic appeal and this is why he invested a large portion of the profits in design and marketing as well as in research. Olivetti believed in the importance of redistributing profits in the community that had generated them and, even in times of crisis, decided not to sacrifice the surplus workforce but expand the commercial network instead. The eyes of those who lived the Olivetti experience at the bottom, and others, reveal nostalgia based on pride and the social advances made possible by facilitated access to education plus incredulity at the avant-garde nature of the social services available and at how these work conditions could improve an employee’s quality of life and “happiness”. The outcome of these improved material conditions and the cultural growth was, however, 50 years lived in a permanent state of bereavement. As the sociologist Luciano Gallino, who worked at Olivetti from 1956 to 1971, has said, “everyone expected everything from Adriano” in a lasting psychological dependency that paralysed initiative and drive. The immaterial legacy left by Adriano Olivetti is of immense value in these parts because it is here, in border country, that Camillo’s factory, an innovation in an area dominated by textile production, and then Adriano’s utopian community enjoyed their first successes.

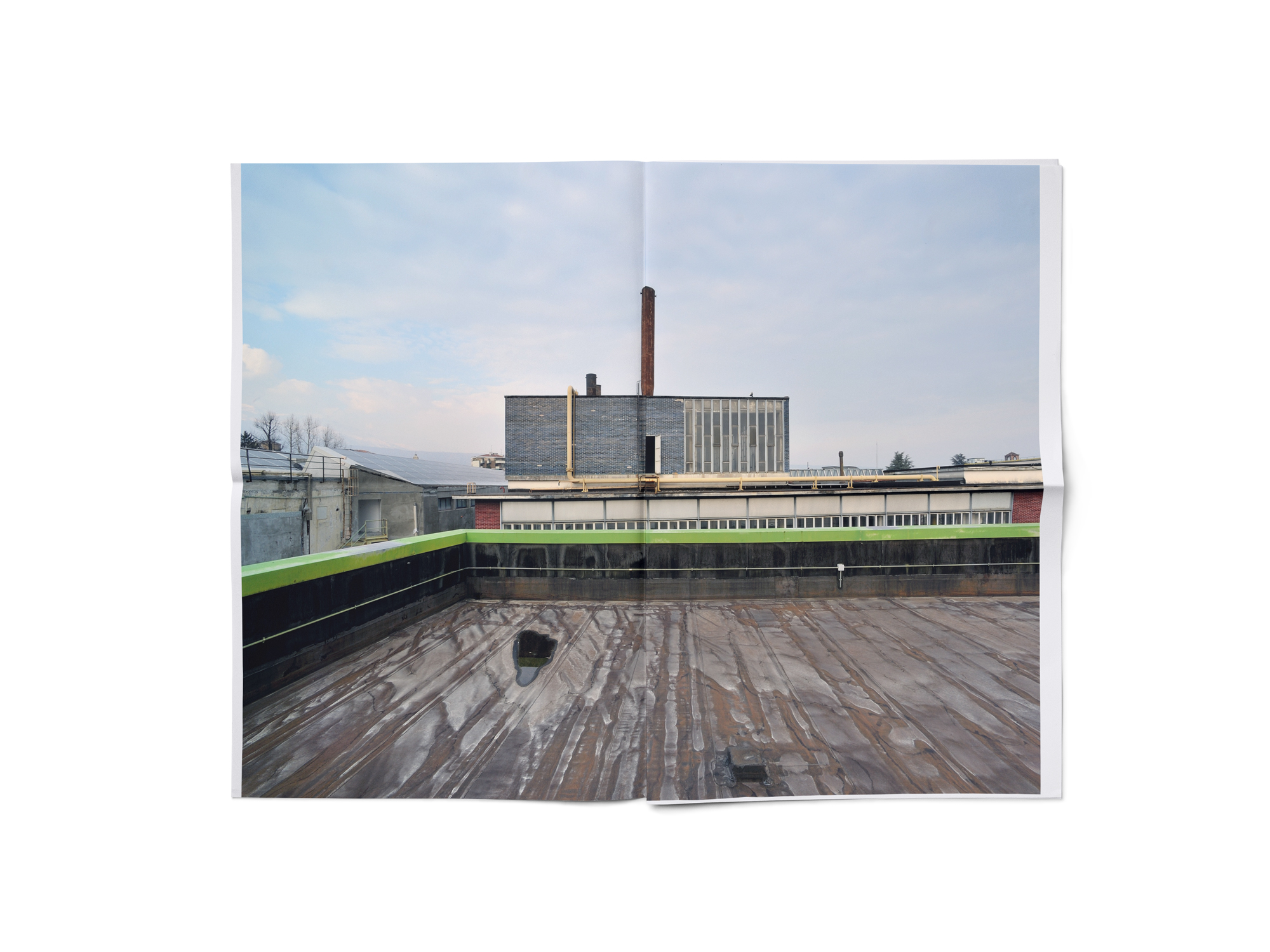

Yet, today, all around the city you feel a sense of resignation and demolition as, year after year, the estate agents that manage the former-Olivetti properties sell off pieces of history before the very eyes of the local government that controls MAAM, the open-air museum of company architecture. All this happens without the emergence of any opinion movement. Safeguarding 20th-century architecture without turning it into a museum, in the knowledge that conversions involve upgrading that must be granted while also raising the awareness of the multinationals, which now own it, as to the historic and symbolic value of these buildings and, as a result, defending the idea they express is the challenge posed by the UNESCO candidature of Ivrea as a company town. At the same time, we must retrieve and rethink, on the basis of today’s technology, practices that are still valid, such as rooting companies in their area and the application of part-time-farming, with the ensuing respect for the landscape that came when employees were not uprooted from their homes — often in remote mountain areas — or from the agricultural work that was in their DNA because a widespread company transport network covered the Canavese area. Courses and recourses of history. When at his best, Olivetti did not join the Confindustria (the Italian employers’ federation) meaning he was up against the capitalists, who could not understand why Adriano did not give profit total priority, but also the Marxists, who accused him of paternalism. Not joining the Confindustria was a firm decision that would, of course, have the opposite effect for a well-known national company today. In today’s situation, in which the only realistic work flexibility consists in the employee bowing to the company’s will, thinking about the Olivetti experience would reopen people’s minds to an experience that was real but that now seems surreal: the rebuilding of the city on a human scale and not only for profit. It is exactly what the spirit of our sick times calls for.

Text by Fulvia Grandizio © 2012